Prairies are NOT a monolith

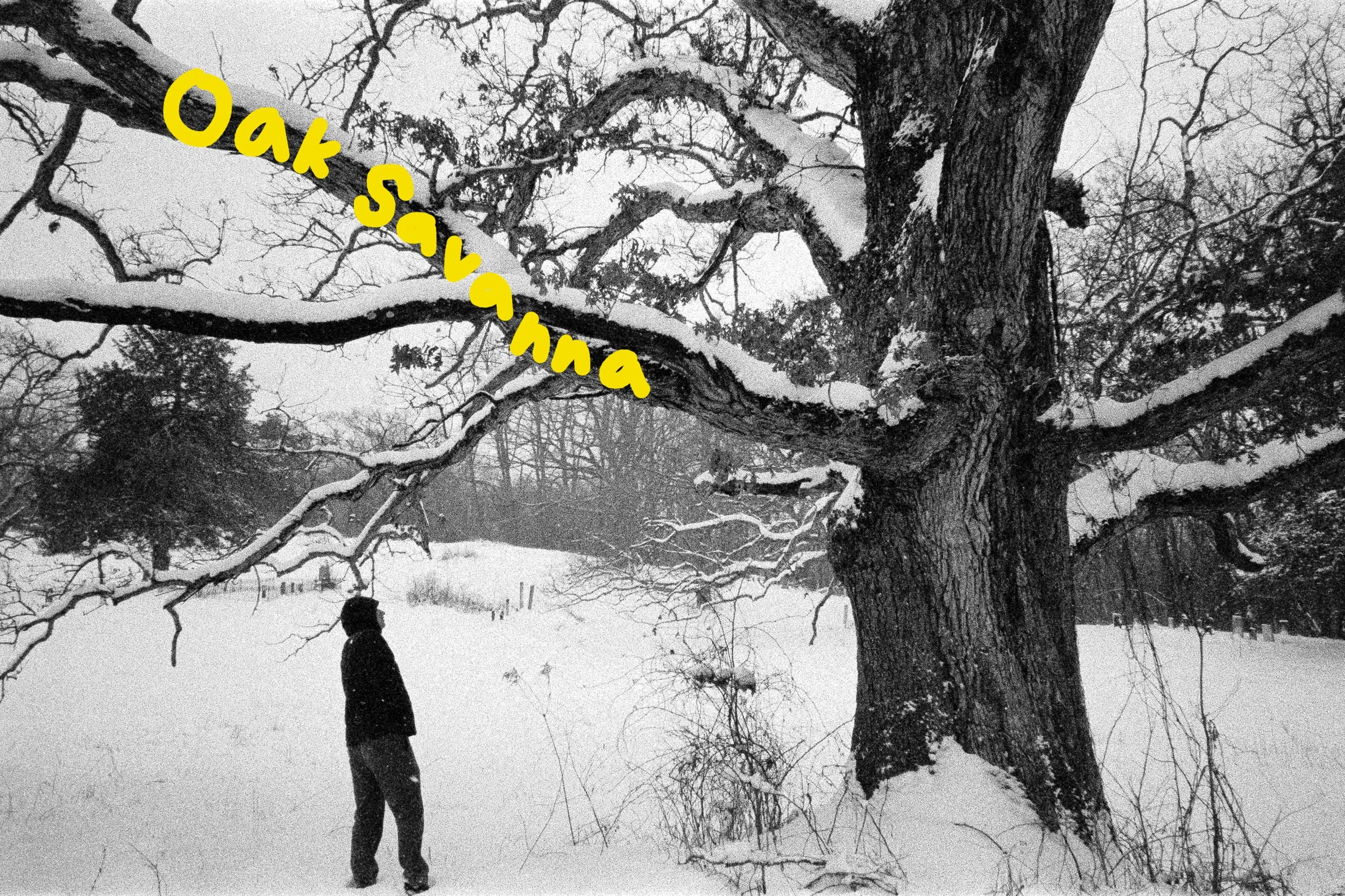

Remnant oak savanna in Eastern Iowa

Charles Dickens, a world-renowned British author, had little positive to say about the North American prairies during his visit to Illinois during the 1800s. Of the prairie, Dickens said, “its very flatness and extent, which left nothing to the imagination, tamed it down and cramped its interest. I felt little of that sense of freedom and exhilaration which a Scottish heath inspires, or even our English downs awaken. It was lonely and wild, but oppressive in its barren monotony.” The term he used that really stuck with me, however, is his description of the prairie as “the great blank”.

This view completely misses the diversity and variety of prairie ecosystems. Dickens, like so many others, sees the prairie as one entity. To me, this is like describing the Siberian taiga, the Amazon rainforest, and the Florida mangroves as “all forests” without distinguishing between the three because they all have trees. Ridiculous right? And while North American prairie ecosystems may not be quite as different from each other as taiga and rainforest, there is an acknowledgement of diversity and variety that is completely lost when it’s all lumped together simply as prairie.

The prairie that I worked at : )

I want to show you that prairies are much more beautiful and varied than people give them credit for.

To begin, the North American prairie generally varies from East to West. This change can generally be viewed as a change in the general height of vegetation and species composition. Prairies are shortest in the west, tallest in the east, and somewhere in between in the middle. I think it’s easiest to visualize this with an imaginary road trip across the U.S from Ohio to Wyoming.

On your road trip west, when traveling along Interstate 80, you will enter substantial bits of the Tallgrass prairie region starting in Indiana. In Illinois, you will be firmly within the tallgrass prairie, and this will carry you all the way across the Mississippi River, through Iowa, across the Missouri River, and into Nebraska.

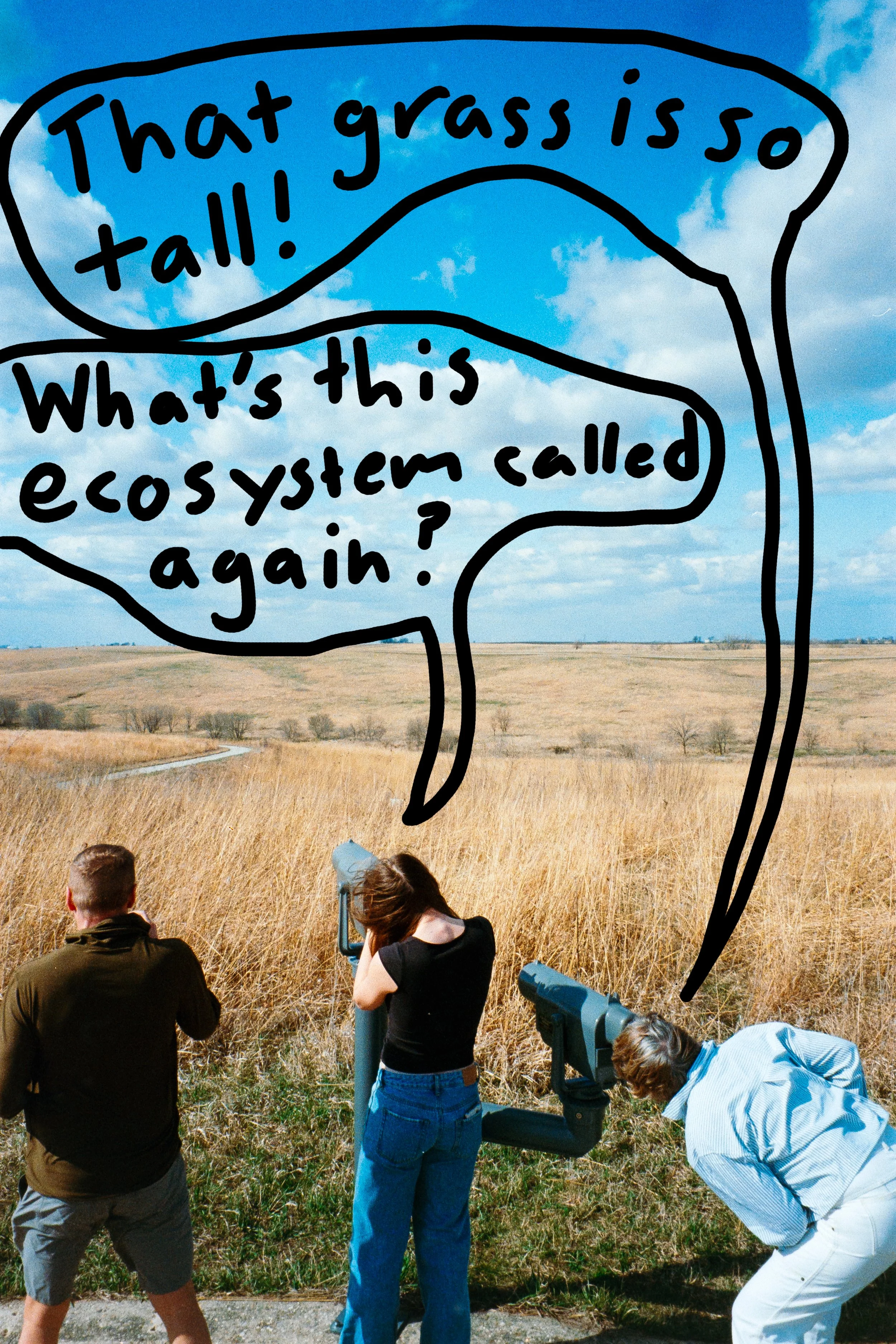

Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge in Central Iowa, one of the largest tallgrass prairie restorations in the country.

Also at Neal Smith!

In central Nebraska, you will transition from the tallgrass prairie to mixed-grass prairie. This prairie is characterized by a mix of tallgrass and shortgrass (subtle foreshadowing) prairie species.

A mix of remnant and restored prairies at TNC’s Platte River Prairies Preserve in Nebraska

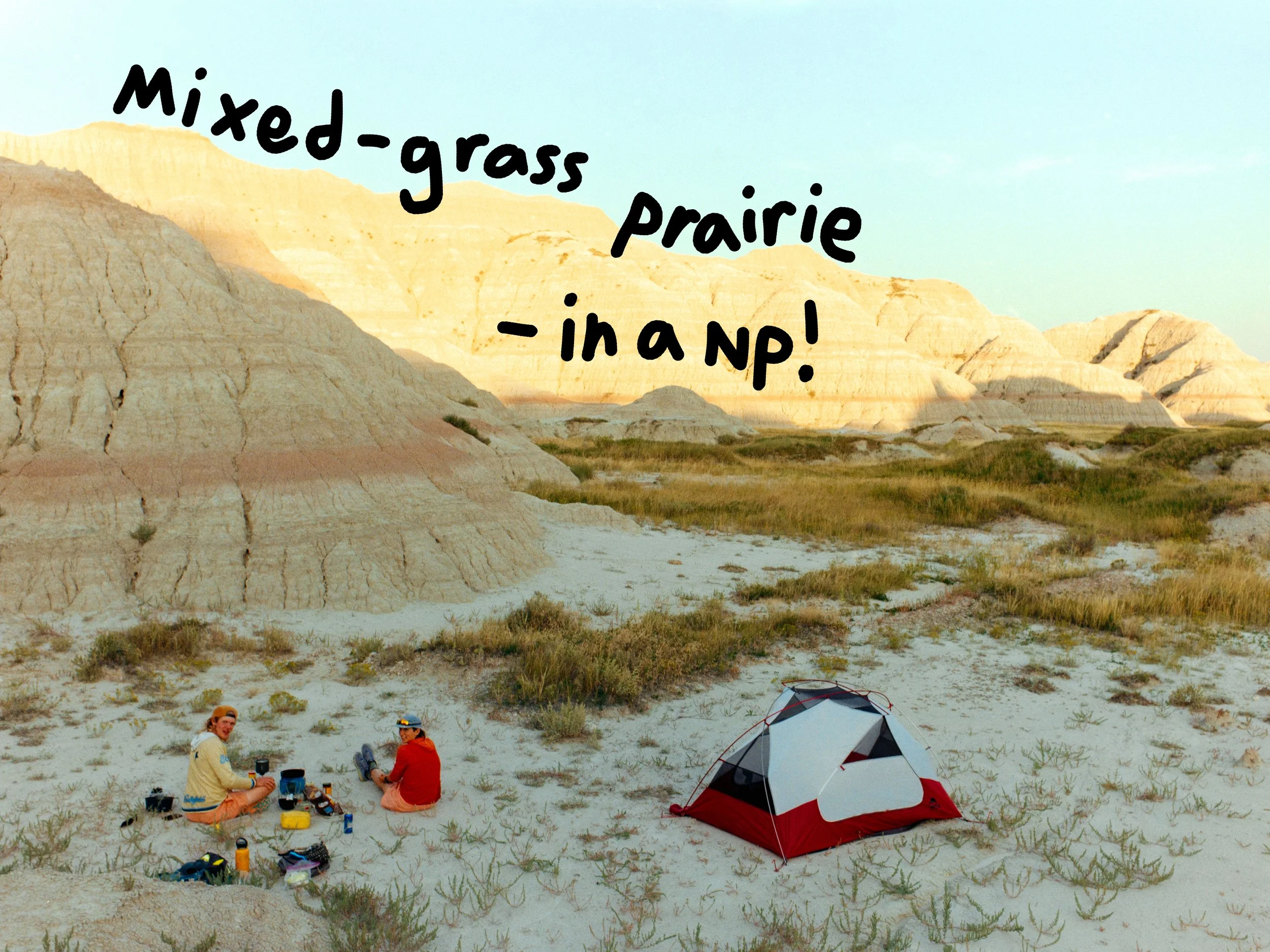

Backpacking in the mixed-grass prairie of Badlands National Park (ignore how sunburnt I am)

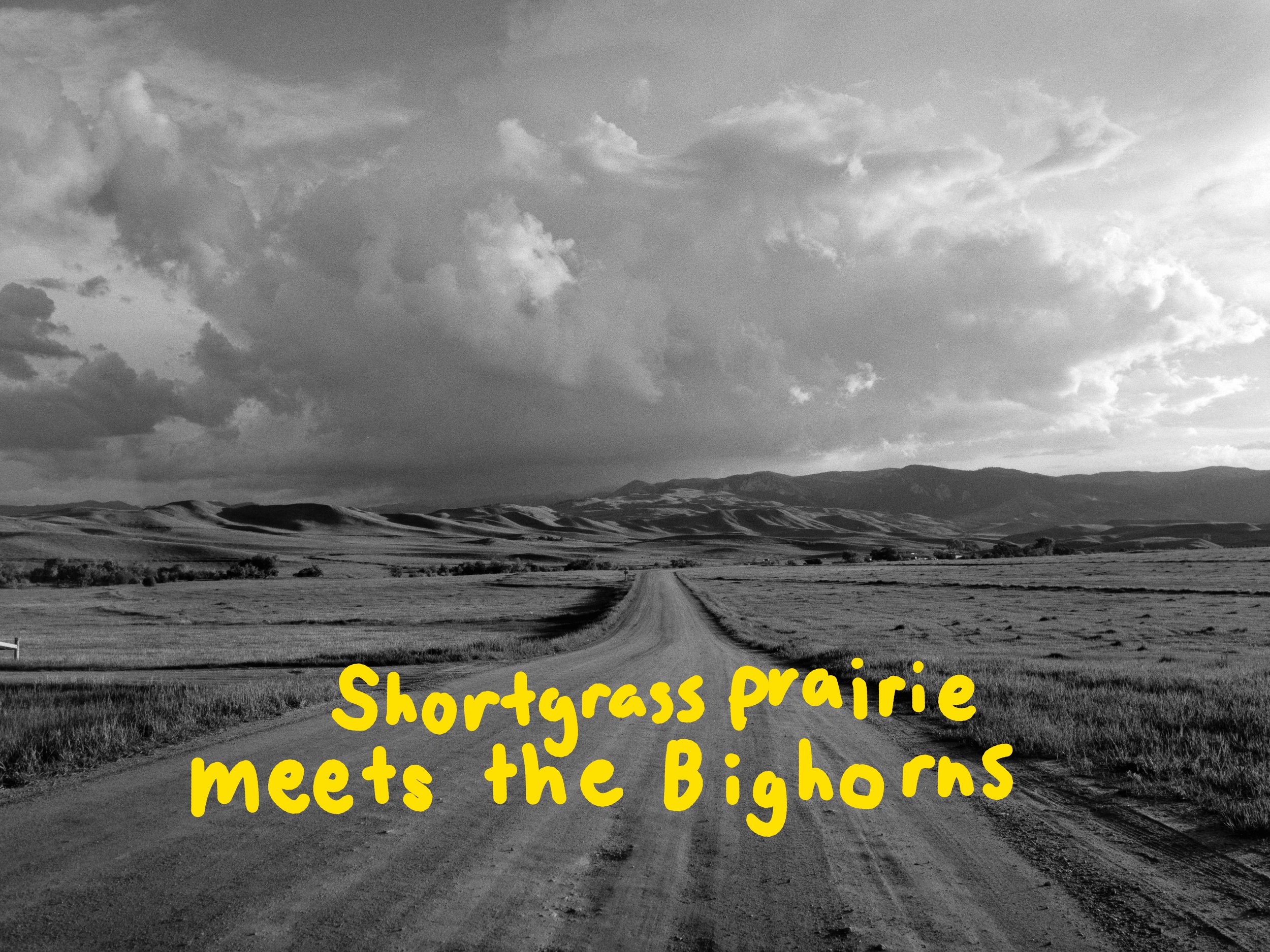

Eventually, you will hit the shortgrass prairie in the Western part of the state. The shortgrass prairie will carry you all the way to the edge of the Laramie Mountains (or Bighorns farther north) in Eastern Wyoming before it finally succumbs to granite boulders, ponderosa pines, and sagebrush.

Irrigated fields interspersed with shortgrass prairie near Story, Wyoming.

At the edge of the great plains, looking east towards the tallgrass prairie so very far away

Although the differences between the tallgrass, mixed-grass, and shortgrass prairie are wonderful and worth highlighting, I’m more interested in the local diversity of prairie ecosystems. This is the kind of ecosystem diversity that Charles Dickens could have experienced with only a short wagon ride. It’s also the kind of diversity that you can experience close to home if you live in a prairie state!

I just so happen to be from a tallgrass prairie state (Iowa) and happen to have lived in a few more of them (Minnesota and Illinois), so I’m better equipped to speak on the variety within the tallgrass prairie than the shortgrass or mixed-grass prairie. This is BY NO MEANS an exhaustive list of different kinds of prairies, nor are these classifications particularly scientific. I would guess, however, that if you use these terms around a prairie nerd, then they will know what you mean.

A little goat prairie near Maiden Rock, Wisconsin (right across the river from Red Wind, Minnesota)

Goat prairies are little remnants that exist on the edges of bluffs, cliffs, or other steep terrain. Their rugged environments prevented them from being tilled by farmers, and (sometimes) have allowed them to stay free of tree encroachment, even in the absence of fire.

An amazing remnant goat prairie in Whitewater WMA, Minnesota

This one shown in the B&W photo is home to some interesting species, like downy paintbrush, dotted gayfeather, and perhaps the only remnant population of pale-purple coneflower in the state of Minnesota.

A remnant white oak in a settler graveyard near Rochester, Iowa

Remnant oak savanna is one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world. According to The Nature Conservancy, “less than 65,000 acres of oak savanna remain in the Midwest—two-tenths of one percent of the pre-settlement savanna.” This oak, along with a few others, overlooks a cemetery and remnant prairie in rural Iowa.

Oak savannas, like this one, are home to a beautiful mix of woodland and prairie species. Mayapples, geraniums, and columbines cling to the shade offered by the trees. Prairie shooting stars are ubiquitous here, in both sun and shade. Rarer prairie species like bastard toadflax and puccoons stay in the sun, away from the circles of shade underneath the oaks.

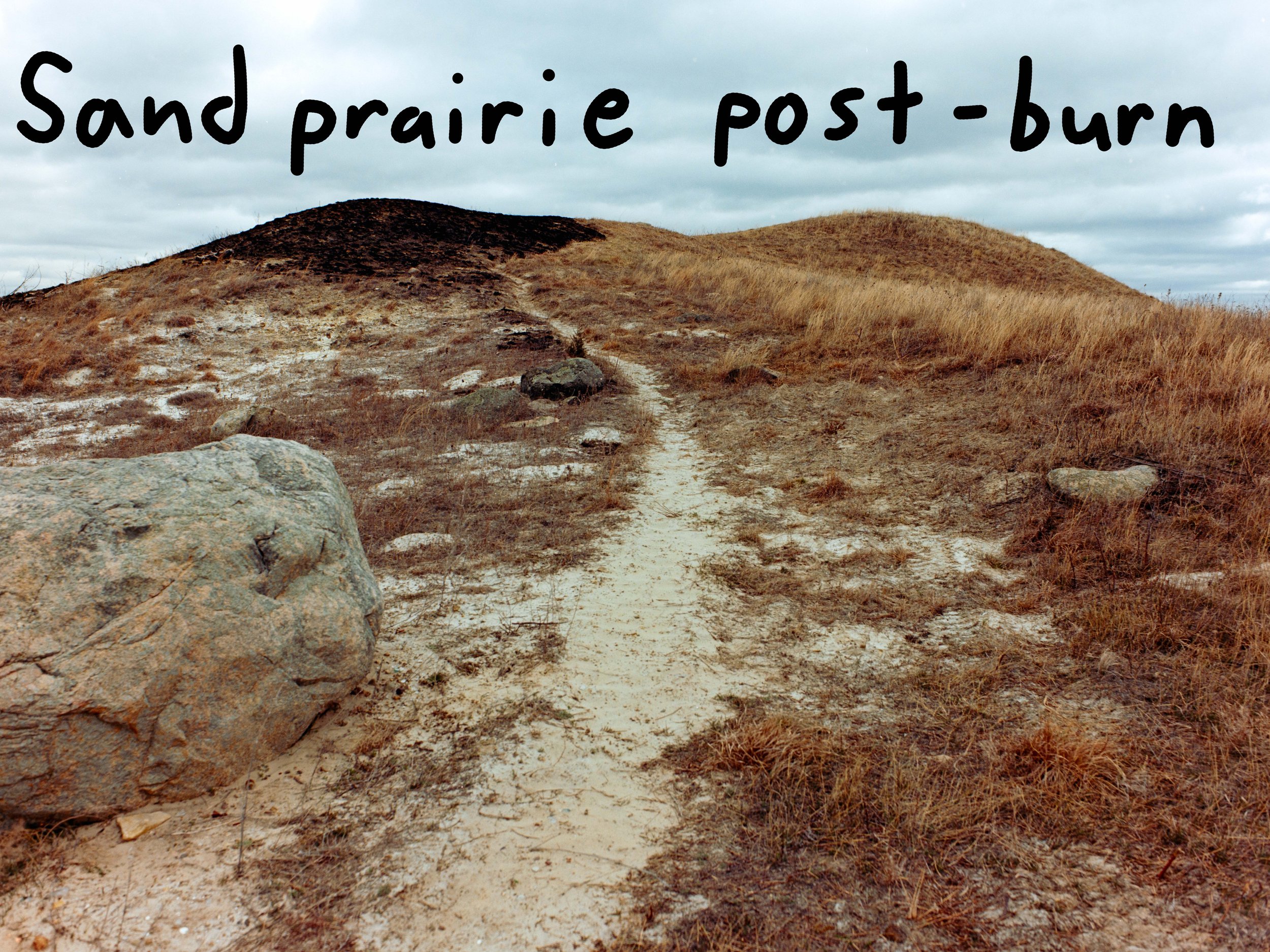

McKnight Prairie, a remnant sand prairie, in Southeast Minnesota

This remnant sand prairie is currently surrounded by cornfields, but its sandy and rocky soil prevented it from being farmed. The return of fire has helped return this formerly degraded prairie to a much healthier state.

Two interesting flowers that can be seen here are prairie smoke and pasqueflower. These can both be seen blooming in March and April before anything else in the prairie has even turned green again!

A wet prairie in Chicago, Illinois

Wet prairies are… wet! This one is right on the shore of Lake Michigan! Wet prairies can be home to fun species like swamp lousewort and white turtlehead. The blue/purple flowers that you see in this particular photo are great blue lobelia!

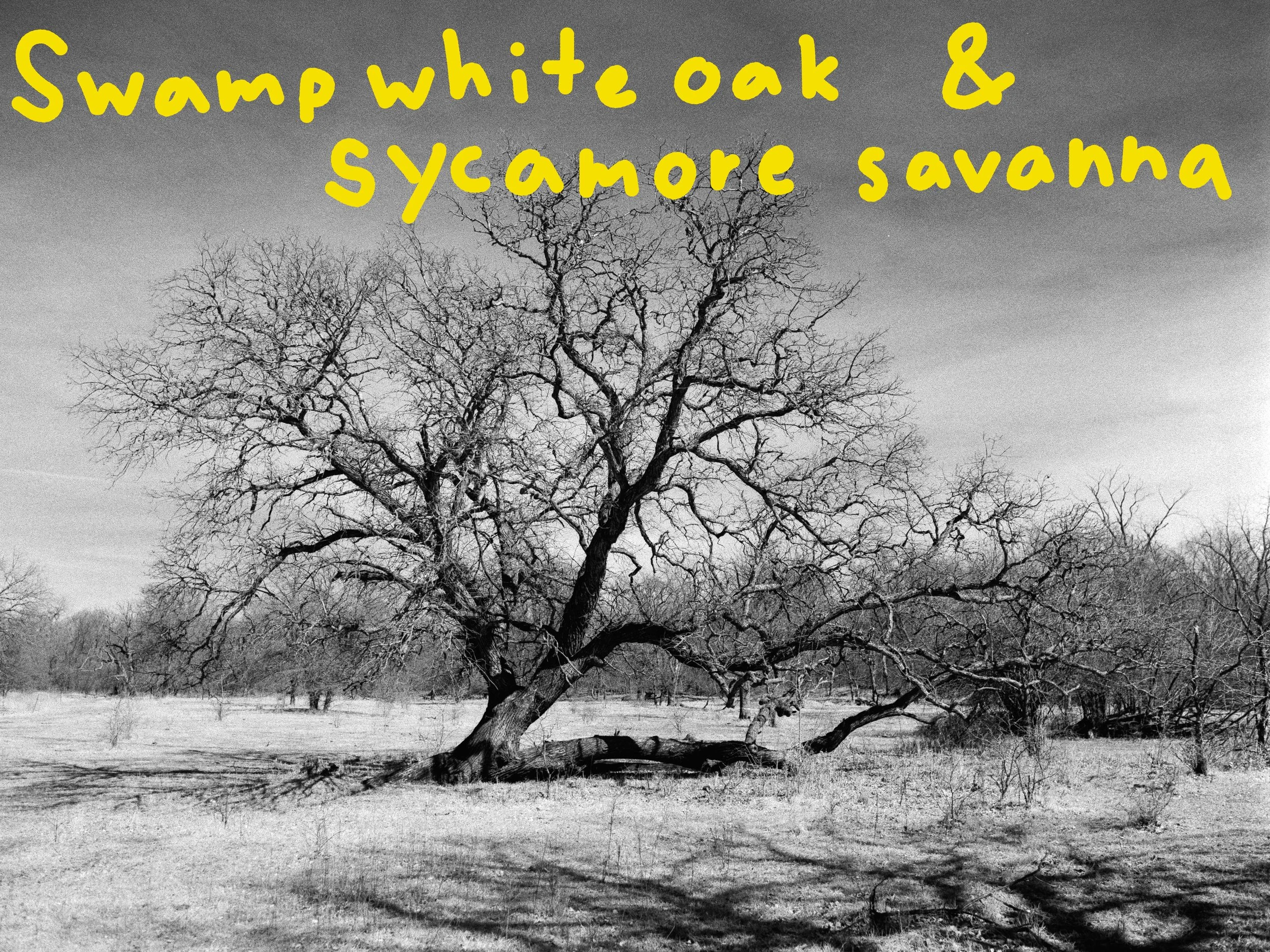

TNC’s Swamp White Oak preserve in southeast Iowa

This is a remnant floodplain savanna along the Cedar River. Unlike many other oak savannas that are generally home to white and bur oaks, this one is home to swamp white oaks and sycamore trees! It’s also home to fringed prairie orchids and one of the most diverse herptile communities in Iowa.

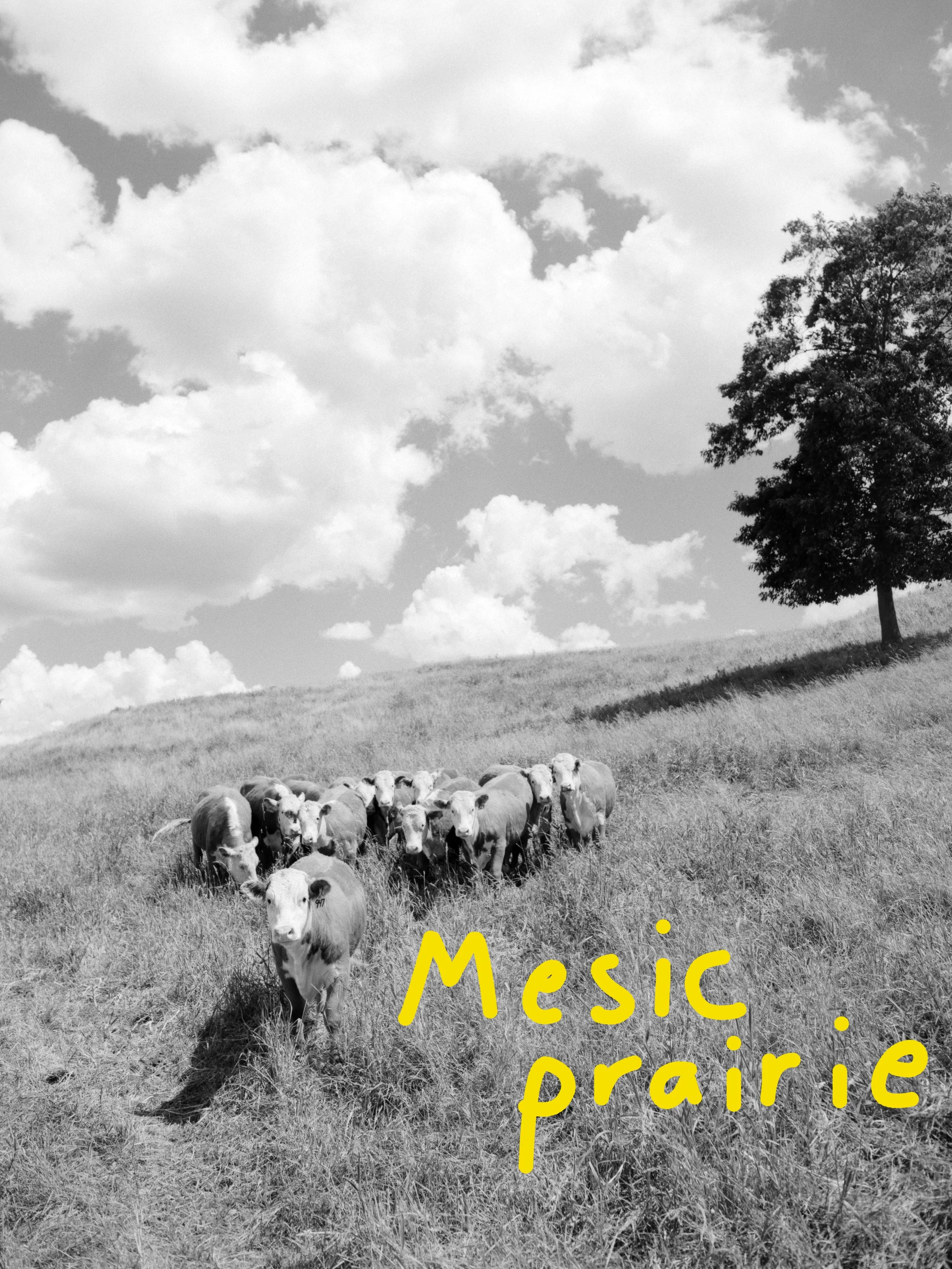

A remnant prairie in Southeast Minnesota, where grazing is employed as a management strategy

Lastly, mesic prairie is not too dry and not too wet. It’s Goldilocks prairie, if you will. Mesic prairie was also the most common type of prairie before colonization, but where mesic prairie grows also happens to be the perfect place for corn and soybeans to grow as well. It’s no coincidence that about 86% of the land in Iowa was estimated to be prairie before colonization, and currently, about 86% of the land in Iowa is devoted to agriculture.

Dixon Prairie, The Chicago Botanic Garden

The complete transformation of prairie to farm fields in Iowa is similar to the fate of the prairie in other tallgrass prairie states. Of the total tallgrass prairie that existed before European colonization, less than one percent remains today. Colonizers rapidly destroyed the prairies that indigenous people had stewarded (and still do) for thousands of years over the course of only a few decades. This destruction happened exceedingly rapidly, with little to no thought for the consequences. I’m sure this rapid alteration of the landscape didn’t make Charles Dickens blink twice (can you tell I’m not a fan?). In my home state of Iowa, the amount of tallgrass prairie left is even lower; under one-tenth of one percent.

The bits of original prairie that remain untilled, unfarmed, and undeveloped are collectively referred to as “remnants”. Many of the large remnant prairies that we have left weren’t preserved intentionally, but were rather simply unfarmable land. These are places like the Loess hills of Western Iowa and the Flint Hills of Kansas. These prairies safeguard a wealth of biodiversity, support rare species, harbor remnant trees older than the U.S. Constitution, and give us an idea of what the tallgrass prairie looked like 300 years ago.

These generally small prairies aren’t large enough to fulfill all the ecosystem services they need to, however. They are also often isolated and susceptible to degradation from invasion by invasive species or encroachment by woody trees or shrubs.

Lots of round-headed bush clover in a remnant prairie in Southeast, Minnesota

Prairie restoration, the practice of planting native prairie plants into an area to try an re-create aspects of remnant communities, is a partial solution to this problem. Prairie restoration can help buffer remnant prairies from invasion by invasives, connect isolated habitats to enable to flow of animals and plant genetic material, and re-create larger habitats that are required by grassland birds. They also provide WAY MORE ecological services than the farm fields they often replace. Prairie restoration is an ongoing process across the Midwest, and with a little looking, you can likely find one near you!

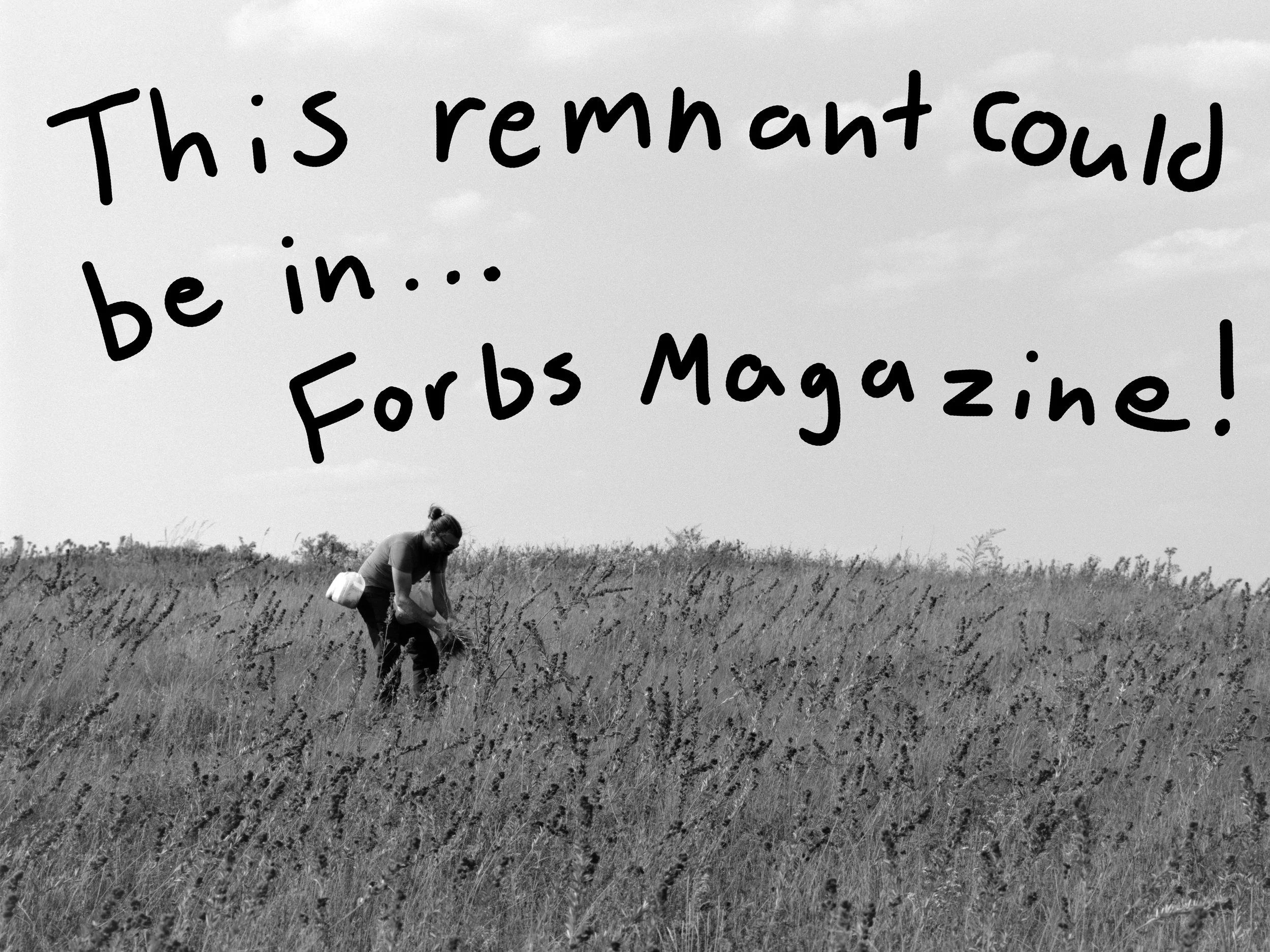

Unfortunately, prairie restoration can’t perfectly replace the prairies that we have lost. Restored prairies generally have much lower biodiversity compared to remnant prairies, and they tend to be overrun with a few dominant grass species (Big bluestem, switchgrass, golden feather grass, etc…). These grasses out-compete native forbs (flowers), the group responsible for most of a prairie’s diversity and pollinator services. The flower species in restorations are also generally more similar to each other than the flower species in remnants, even if there is the same total number of species. For example, a restoration and a remnant may both have 10 species in the same-sized area, but all 10 of the species in the restoration might be from the aster family, while the 10 species in the remnant might represent 6 different plant families.

Practice burn in a tiny prairie restoration in Southeast Minnesota

A remnant prairie in Southeast Minnesota

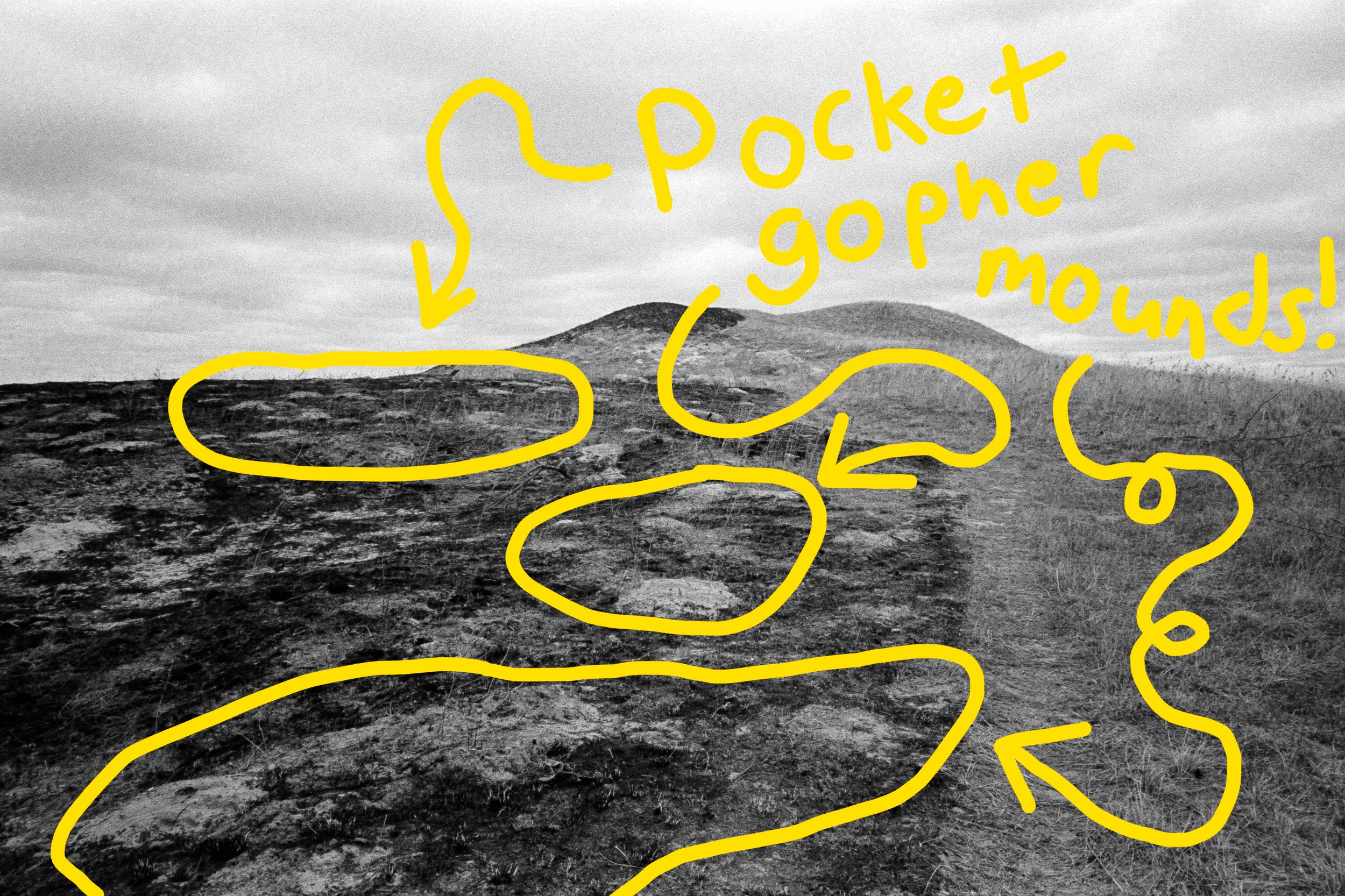

There are also many species that exist in remnant prairies but are rarely, if ever, found in restored prairies. These species include many plants, like a variety of orchids, bastard toadflax, paintbrushes, and many more. There are even some animal species, like pocket gophers, that are often missing from restorations but are common in remnants.

These acknowledgements of the faults of prairie restorations may make me appear anti-restoration; however, that’s certainly not the case! It’s simply important to understand the differences between remnants and restorations so that we can be better at mitigating those in the future!

Pocket gopher mounds are easy to spot in this Southeast Minnesota remnant prairie after its been burned!

Tallgrass prairie restorations are WAY better than nothing, but they certainly cannot replace remnant prairies. Prairie remnants are just so diverse that we shouldn’t expect to be able to perfectly recreate them with only a few years of effort. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, however, and well-managed prairie restorations are getting pretty good! Prairie restoration is certainly a cause worth supporting.

So now that you know that tallgrass prairies are beautiful and diverse, but also extremely endangered, you may be asking …

Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) in a prairie remnant in Southeast Minnesota

“What can I do about it?”

Here are a few suggestions!

Never listen to anything Charles Dickens has to say ever again.

Learn about the prairies near you! You need to know they exist before you can do anything to help…

Volunteer at a local conservation organization! There are often opportunities to help collect or clean seeds (two of my favorite activities) that will be used for future prairie restorations.

Plant native plants in your yard! You can start your own little prairie restoration right at home. It’s a great way to learn about plants and help the environment!

Learn more about the history of the land you are on! Who was there before you? (and is still here) Who lived with the prairie? Who destroyed it?

My dog investigating the prairie plants in my parents’ yard

Thanks for sticking it out to the end of the world’s biggest blog post! I hope you learned something, I hope you enjoyed the photos that I’ve put so much of my heart into, and I hope you will go check out a prairie near you!

Much love!

- Kelby Anderson

The end! (Of my blog, NOT of the prairie!)